The Mind is Our Own Hidden Trap in Decision Making

Decision making is a process (or a necessity) which occurs whenever we find ourselves at a point in which our current and desired states do not match. There is a gap to be explored. And a decision to be made. Decision making is one of those areas of life that are blurred, confusing, and extensively researched (especially in the business world). Yet, despite having some clear models depicting how we make and elaborate decisions (i.e. rational and bounded rationality models of decision making), this seems to be a field requiring a deep understanding of the human mind. Proper decision making calls for open-mindedness, integrative thinking, trade-offs, self awareness of our own biases. Decision making can become a skill, if practiced deliberately and mindfully, which can get better with experience.

Biases and heuristics in decision making are prominent, as they are in other areas of life such as negotiation, judgment, thinking. And while disposing of mental flaws seems to be inherent to the human condition, increasing awareness of our own distortions can make the difference in developing as an individual, and making more examined decisions.

Why We Make Decisions

When we are faced with choices, however broad their scope, there is a weird situation arising. The present tangles with the future and the past at the same time. The present state we experience is, for some valid reason we have identified, to be changed. To do so (change the present state), we begin to think about options in the future, which, however, are merely born in imagination. Thinking about the future, we may feel a slight discomfort or anxious thoughts arising in the mind and body. Uncomfortable state that may stem from past experiences when we found ourselves on the verge of making decisions, or having made a decision and regretting it; or that time in which we picked the right choice. We get into freeze, flight, fight state. All this may happen in the mind, while we are still in the present moment, looking for possible solutions, and hoping for the best outcomes to happen. Some degree of anxiety is only useful if it propels action in the present moment. Hope is, above all, fear in disguise.

Think about someone wanting to find a new job (either because they want to leave their existing workplace or because they are unemployed). This is a decision making situation. There is a current state which needs to be changed. There is uncertainty. The person looking for a job may feel anxious, or hopeless, or excited (the degree of which also depends on personality traits). Chances are, however, that a job is much more likely to be found if you take action in the present moment, with a clear system and strategy in mind. Ruminating about the past or getting lost in the future are not useful mental activities, if no action is taken in the present moment in order to maximize the chances of getting a new job position. So, you may begin breaking down the process of finding a job. Maybe, you say to yourself, you can start from putting together a proper resume, or updating it (if you had not touched it in a while), one step at a time. And you may also ask for help from one of your acquaintances who seems to be skillful at this. Then, you may start looking for career opportunities on dedicated platforms such as LinkedIn or Indeed. And send job applications that are properly thought-after, so to maximize your chances of success in landing an interview.

How We Make Decisions

The process of decision making can be as convoluted or simple as you want it. As Daniel Kahneman reminds us in his book "Thinking, Fast and Slow", there are two main macro areas in our brain driving our behaviors and decisions: the limbic system (system 1), and the prefrontal cortex (system 2). System 1 (limbic system) is the more primitive, impulsive side of the brain, which comes into play instantly whenever we are faced with a new situation, and which acts quickly, without thinking. System 2 (prefrontal cortex), on the other hand, is the "slow thinking" part of our brain. It is the system that comes into play after system 1, and which attempts to employ rationality, reflection, context. The problem with both system 1 and 2 is that they are both subject to bias and systemic flaws. The limbic system is wired toward survival and acting fast in order to avoid danger or death. The prefrontal cortex employs rationality to a certain extent, in terms of our individual capacity for rationality, which is always limited by cognitive bias, cultural and social norms, the past, the future.

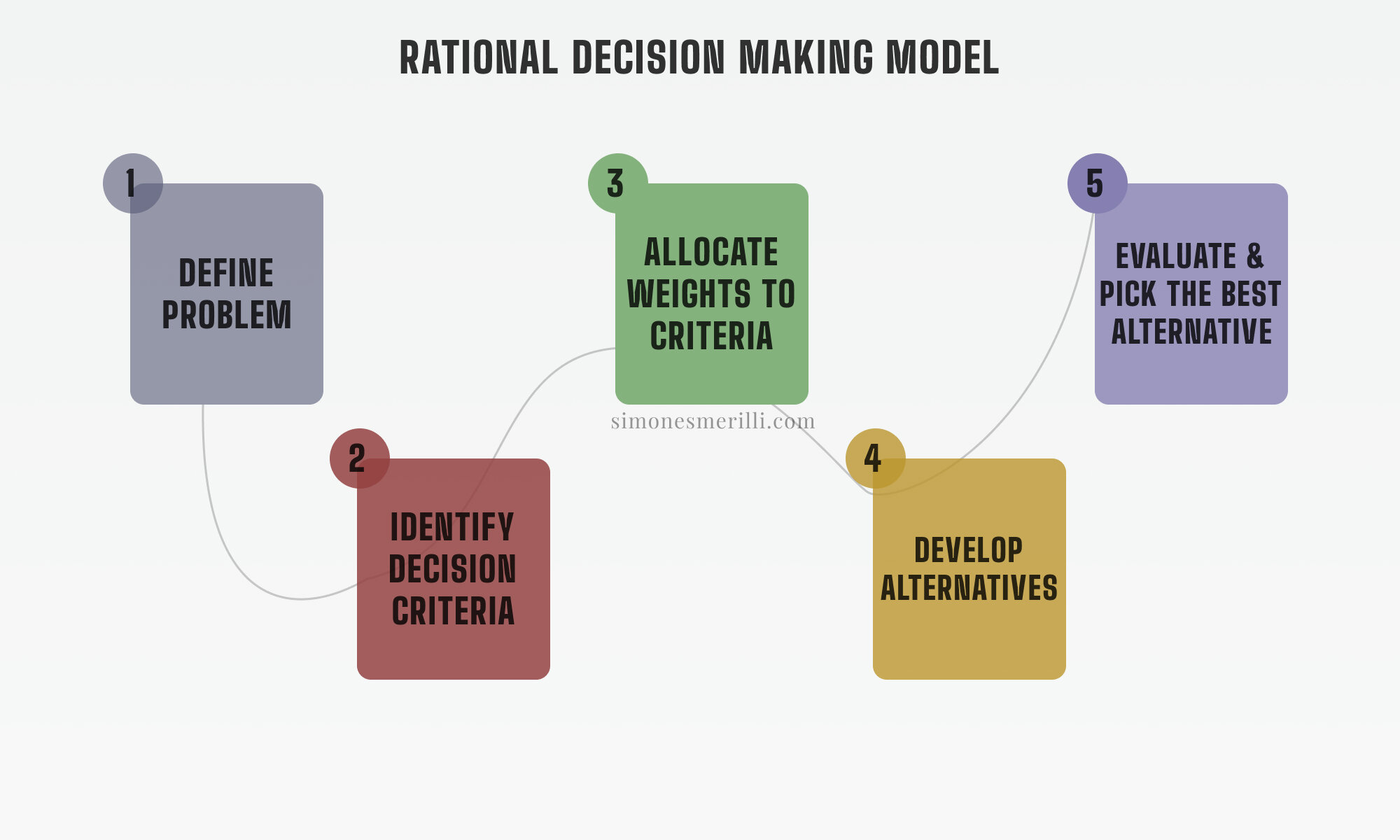

In decision making, there are two frameworks developed to depict our decision process: the rational decision making model, and the bounded rationality framework.

Rational Decision Making Model

The rational decision making model is the oldest model for decision making. According to this framework, we make decisions following logical thinking and rationality, hence maximizing our chances of making the most optimal decisions. This model of decision making identifies six main steps to decision making (Tan Lydia, 2020):

Define the problem

Identify the decision criteria

Allocate weights to the criteria

Develop the alternatives

Evaluate the alternatives

Select the best alternative

As a consequence of the complete rationality depicted by the model, decision makers are assumed to have complete information available, hence free will, and they pick the option with the highest utility. Implementing the rational decision making model in our life and work decisions can have the advantage of providing a clear structure to follow, as well as making the reasons behind our decisions transparent. At the same time, acting out the rational model of decision making can result in a long and mechanical process which requires time and excessive effort. In the real world, time and cognitive effort are limited resources, and in the age of digitalization, where decisions must be made very quickly (particularly work decisions, as far as I can tell), most choices are not based on pure rationality. If we also factor in the truth that our reasoning is flawed and we are subject to many cognitive biases, the rational model of decision making becomes even more a mere ideal framework, as opposed to a component of reality.

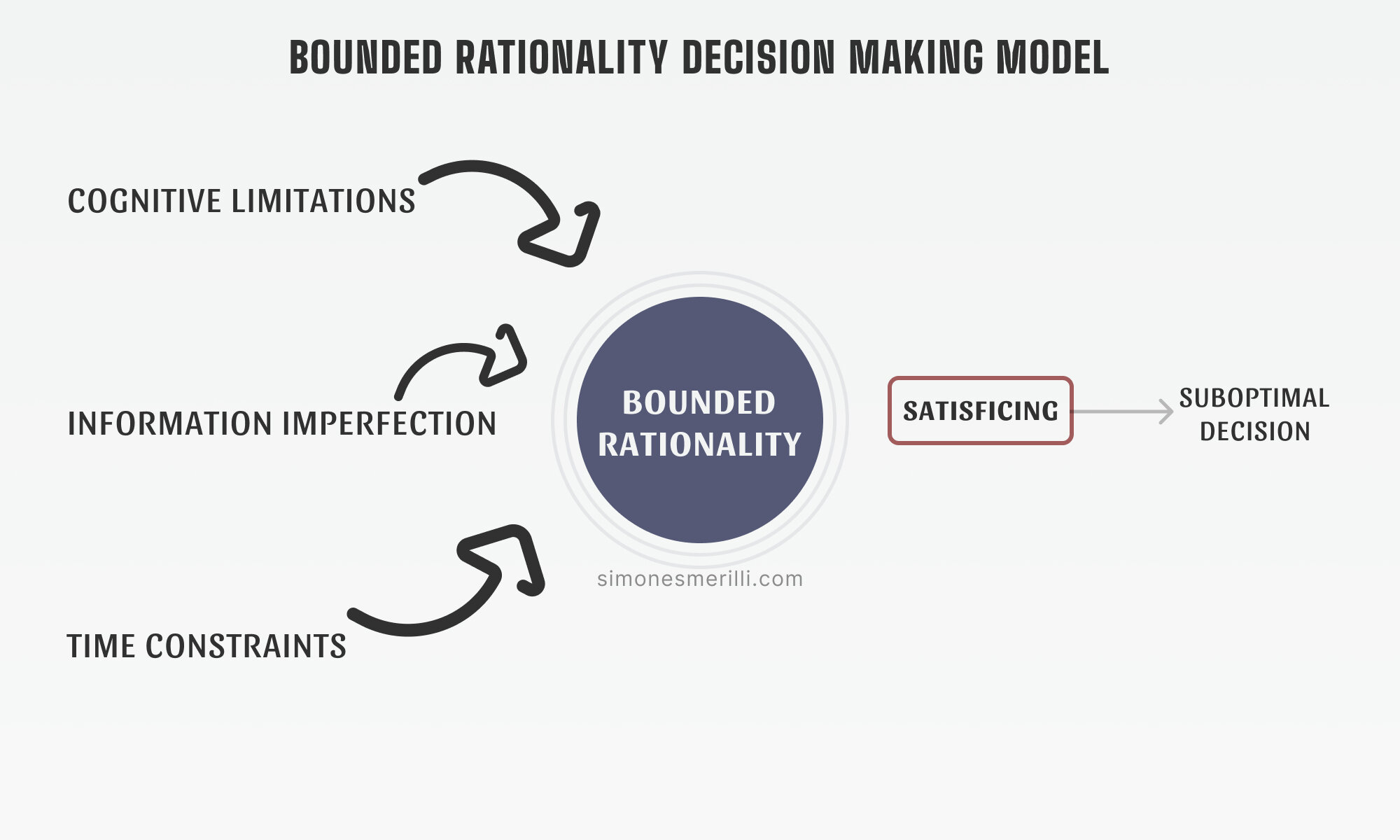

Bounded Rationality Decision Making Model

Enter the bounded rationality decision making model. This model trying to explain the human mind in action when making decisions accounts for our mental, time, and resources limits. For one, bounded rationality postulates that we satisfice in making decisions. Namely, we make decisions that are "good enough". This is because we are not actually aware of all the options out there, and, as a consequence, we simplify the complex problem at hand by reducing it to a level that can be more easily understood. We play the game of decision making within the confines of bounded rationality (Tan Lydia, 2020), choosing the first, most acceptable alternative. So, although the decision making process in the bounded rationality model looks very similar to the process depicted by the rational framework, here there is the realistic assumption that we have limited resources when making decisions. As a consequence, we can only make the best decision for what we have available at the moment of the decision. Our decision can only be as good as our best alternative.

Bias and Heuristics in Decision Making

“In making decisions, your own mind may be your worst enemy.”

When it comes to analyzing decision making in real life, we need to keep in mind that we are biased beings. We constantly fall prey to cognitive bias, heuristics, and distortions of all kinds. These mental flaws escalate even more the higher the stakes and perceived pressure of the decision. Biases and heuristics are inherently engrained in our psyche, and we cannot completely eradicate them. We can, however, bring awareness to them, in order to develop the skill of catching ourselves whenever wrong cognitions are at play in our mind. It is only by being aware of our own biases and keeping an open mind that we can become better at detaching ourselves from the decisions we make, and use our cognitive capabilities to the fullest. In their 1998 article on HBR, Hammond, Keeney, and Raiffa do a great job at illustrating bias in decision making. Some of the most usual biases and heuristics at play in decision making are:

Anchoring: when considering a decision, the mind gives disproportionate weight to the first information it receives. Some of the ways to combat the anchoring trap include: looking at a problem from different perspectives and starting points; seeking information from various sources to widen our framework of reference; being particularly aware of the effect of anchoring in negotiation.

The status quo trap: moving away from the status quo requires taking responsibility and action, thus opening ourselves to criticism and possible regret. "In business, where sins of commission (doing something) tend to be punished much more than sins of omission (doing nothing), the status quo holds a particularly strong attraction" (Hidden Traps in Decision Making, 1998). When making decisions, sometimes maintaining the status quo is truly the best decision to make. However, we do not want to stick to the status quo just because it feels comfortable. We need to remind ourselves of our initial objective and purpose for the decision, with clarity of mind. We can also ask ourselves whether we would choose the status quo, if, in fact, it were not the status quo.

The sunk cost bias: this bias is about making choices that justify past, flawed choices. This bias has to do with our tendency to trying to reduce cognitive dissonance as much as possible in our choices. However, if we are aware of mistakes made in the past, we need to let go of the ego attached to our reputation, and reverse the decisions for the better. We need to remind ourselves that failure is part of the game of life and decision making, and that changing our mind is a good sign of improvement and development.

To rephrase a sentence from the article on HBR cited above, "when it comes to life decisions, there is rarely such thing as a no-brainer". Our minds are always at work, at a subconscious level, influencing the way we judge, behave, negotiate, make decisions. We cannot eradicate our biases from the brain, but we can shine the light of awareness on them, in order to detach ourselves from our worst, inner enemy in decision making: our own psyche.

P.S: intuition also has its role in decision making, as this article depicts comprehensively.

I also write a weekly newsletter. If you found this article meaningful, you may consider signing up and/or checking out previous issues here.ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Decision making | Psychology Today

Organizational Behavior | Robbins & Judge

Thinking Fast and Slow | Daniel Kahneman

Forward Thinking With Roger Martin | The Knowledge Project

SIMILAR POSTS: